DFS Ransomware Guidance - Financial Sector.

The Department of Financial Services (DFS) of New York released a letter outlining how regulated organizations need to cooperate to thwart and lessen ransomware attacks.

The letter outlines nine controls that need to be implemented by regulated companies.

Both regulated financial institutions and the MSSPs (Managed Security Service Provider) who supply them with services should take note of the letter.

MSSPs will need to demonstrate how they can assist their customers in following DFS's guidelines in order to engage with regulated businesses.

Fighting ransomware requires technology that codifies efficient procedures, such as those suggested by DFS, promptly interprets data from various security instruments, and coordinates the necessary reaction.

DFS Analysis of Financial Services Ransomware Attacks.

The advisory letter states that the "good news" is that most ransomware assaults can be avoided, which is unusual when discussing ransomware.

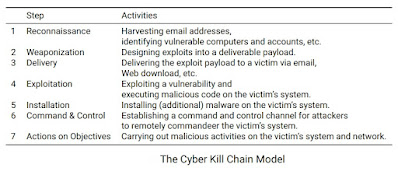

This is due to the fact that ransomware perpetrators often utilize the same methods.

Attackers gained access to the target's network in the 74 recent assaults that the DFS examined by using:

- phishing,

- remote desktop protocols,

- or unpatched vulnerabilities.

In order to launch their ransomware, the attackers would then increase their privileges, often by acquiring and decrypting encrypted passwords.

The advice letter points out that there are well-known defenses worth considering against the ransomware attackers' common tactics that might assist shield their intended victims.

DFS's Ransomware Security Controls for Financial Services Companies Subject to Regulation

The letter outlines nine particular measures that regulated businesses are required to put in place wherever feasible.

The first seven concentrate on avoiding ransomware while the latter two discuss preparing for a ransomware occurrence. The nine controls are listed below:

1. Anti-Phishing education and email filtering.

The advice emphasizes the need of employing both technical and educational tools to safeguard against phishing emails.

2. Patch and Vulnerability Management.

According to the recommendations, businesses should have a written program for controlling vulnerabilities that includes regular security fixes and upgrades.

3. Two-factor identification.

According to the advice, employing MFA for user accounts is successful at preventing hackers from entering the network and growing their rights.

4. Turn off RDP Access.

The guidelines advise regulated companies to limit access to remote desktop protocol to whitelisted sources and deactivate it wherever feasible.

5. Password administration.

Access control and password management are essential for limiting dangerous threat actors, including ransomware.

6. Manage Privileged Access.

According to the recommendations, businesses should rigorously guard, audit, and limit the usage of privileged accounts, and individuals should be granted the least amount of access necessary to carry out their tasks.

7. Response and monitoring.

According to the recommendations, businesses need to have ways to keep an eye on their systems and react to any questionable behavior.

EDR and SIEM are among the proposed techniques.

8. Backups that have been tested and separated.

The advice stipulates that regulated organizations should store several backups, at least one set of which should be separated from the network, in the first control that deals with preparing for an incident (the first seven addressed preventing an occurrence).

Businesses should routinely check their ability to recover systems using backups.

9. An emergency action plan.

Companies should develop incident response plans that particularly target ransomware, according to the recommendations for the second incident preparedness control.

Find Jai on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram

You may also want to read and learn more Cyber Security Systems here.