Title: The Need For Iterative And Evolving AI Ethics Processes And Frameworks To Ensure Relevant, Fair, And Ethical Scalable Complex Socio-Technical Systems.

Author: Jai Krishna Ponnappan

Ethics has strong fangs, but they are seldom applied in AI ethics today, therefore it's no surprise that AI ethics is criticized for lacking efficacy.

This essay claims that present AI ethics 'ethics' is generally useless, caught in a 'ethical principles' approach and hence particularly vulnerable to manipulation, particularly by industrial players.

Using ethics as a replacement for the law puts it at danger of being abused and misapplied.

This severely restricts what ethics can accomplish, and it is a big setback for the AI field and its implications for people and society.

This paper examines these dangers before focusing on the efficacy of ethics and the critical contribution they can – and should – provide to AI ethics right now.

Ethics is a potent weapon.

Unfortunately, we seldom use them in AI ethics, thus it's no surprise that AI ethics is dubbed "ineffective."

This paper examines the different ethical procedures that have arisen in recent years in response to the widespread deployment and usage of AI in society, as well as the hazards that come with it.

Lists of principles, ethical codes, suggestions, and guidelines are examples of these procedures.

However, as many have showed, although these ethical innovations are exciting, they are also problematic: their usefulness has yet to be proven, and they are particularly susceptible to manipulation, notably by industry.

This is a setback for AI, as it severely restricts what ethics may do for society and people.

However, as this paper demonstrates, the problem isn't that ethics is meaningless (or ineffective) in the face of current AI deployment; rather, ethics is being utilized (or manipulated) in such a manner that it is made ineffectual for AI ethics.

The paper starts by describing the current state of AI ethics: AI ethics is essentially principled, that is, it adheres to a 'law' view of ethics.

It then demonstrates how this ethical approach fails to accomplish what it claims to do.

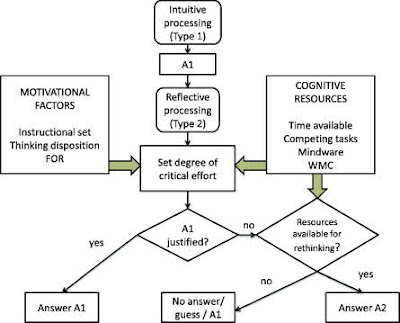

The second section of this paper focuses on the true worth of ethics – its 'efficacy,' which we describe as the capacity to notice the new as it develops on a continuous basis.

We explain how, in today's AI ethics, the ability to resist cognitive and perceptual inertia, which makes us inactive in the face of new advancements, is crucial.

Finally, although we acknowledge that the legalistic approach to ethics is not entirely incorrect, we argue that it is the end of ethics, not its beginning, and that it ignores the most valuable and crucial components of ethics.

In many stakeholder quarters, there are several ongoing conversations and activities on AI ethics (policy, academia, industry and even the media). This is something we can all be happy about.

Policymakers (e.g., the European Commission and the European Parliament) and business, in particular, are concerned about doing things right in order to promote ethical and responsible AI research and deployment in society.

It is now widely acknowledged that if AI is adopted without adequate attention and thought for its potentially detrimental effects on people, particular groups, and society as a whole, things might go horribly wrong (including, for example, bias and discrimination, injustice, privacy infringements, increase in surveillance, loss of autonomy, overdependency on technology, etc.).

The focus then shifts to ethics, with the goal of ensuring that AI is implemented in a way that respects deeply held social values and norms, placing them at the center of responsible technology development and deployment (Hagendorff, 2020; Jobin et al., 2019).

The 'Ethical guidelines for trustworthy AI,' established by the European Commission's High-Level Expert Group on AI in 2018, is one example of contemporary ethics efforts (High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence, 2019).

However, the present use of the term "ethics" in the subject of AI ethics is questionable.

Today's AI ethics is dominated by what British philosopher G.E.M. Anscombe refers to as a 'law conception of ethics,' i.e., a perspective on ethics that treats it as if it were a kind of law (Anscombe, 1958).

It's customary to think of ethics as a "softer" version of the law (Jobin et al., 2019: 389).

However, this is simply one approach to ethics, and it is problematic, as Anscombe has shown. It is problematic in at least two respects in terms of AI ethics.

For starters, it's troublesome since it has the potential to be misapplied as a substitute for regulation (whether through law, policies or standards).

Over the previous several years, many authors have advocated the following point: Article 19, 2019; Greene et al., 2019; Hagendorff, 2020; Jobin et al., 2019; Klöver and Fanta, 2019; Mittelstadt, 2019; Wagner, 2018); Greene et al., 2019; Hagendorff, 2020; Jobin et al., 2019; Klöver and Fanta, 2019; Klöver and Fanta, 2019; Klöver and Fanta, 2019; Klöver and Fanta, Wagner cites the situation of a member of the Google DeepMind ethics team continuously asserting 'how ethically Google DeepMind was working, while simultaneously dodging any accountability for the data security crisis at Google DeepMind' at the Conference on World Affairs 2018. (Wagner, 2018).

'Ethical AI' discourse, according to Ochigame (2019), was "aligned strategically with a Silicon Valley campaign attempting to circumvent legally enforceable prohibitions of problematic technology." Ethics falls short in this regard because it lacks the instruments to enforce conformity.

Ethics, according to Hagendorff, "lacks means to support its own normative assertions" (2020: 99).

If ethics is about enforcing rules, then it is true that ethics is ineffective.

Although ethical programs "bring forward great intentions," according to the human rights organization Article 19, "their general lack of accountability and enforcement measures" renders them ineffectual (Article 19, 2019: 18).

Finally, and predictably, ethics is attacked for being ineffective.

However, it's important to note that the problem isn't that ethics is being asked to perform something for which it is too weak or soft.

It's more like it's being asked to do something it wasn't supposed to accomplish.

Criticizing ethics for not having efficacy to enforce compliance with whatever it requires is like to blaming a fork for not correctly cutting meat: that is not what it is supposed to achieve.

The goal of ethics is not to prescribe certain behaviors and then guarantee that they are followed.

The issue occurs when it is utilized in this manner.

This is especially true in the field of AI ethics, where ethical principles, norms, or criteria are required to control AI and guarantee that it does not damage people or society as a whole (e.g. AI HLEG).

Some suggest that this ethical lapse is deliberate, motivated by a desire to guarantee that AI is not governed by legislation, i.e.

that greater flexibility is available and that no firm boundaries are drawn constraining industrial and economic interests associated to this technology (Klöver and Fanta, 2019).

For example, this criticism has been directed against the AI HLEG guidelines.

Industry was extensively represented during debates at the European High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (EU-HLEG), while academia and civil society did not have the same luxury, according to Article 19.

While several non-negotiable ethical standards were initially specified in the text, owing to corporate pressure, they were eliminated from the final version.

(Article 19, page 18 of the 2019 edition) It is a significant and concerning abuse and misuse of ethics to use ethics to hinder the execution of vital legal regulation.

The result is ethics washing, as well as its cousins: ethics shopping, ethics shirking, and so on (Floridi, 2019; Greene et al., 2019; Wagner, 2018).

Second, since the AI ethics area is dominated by this 'legal notion of ethics,' it fails to fully use what ethics has to give, namely, its correct efficacy, despite the critical need for them.

What exactly are these ethical efficacy, and what value might they provide to the field? The true fangs of ethics are a never-failing capacity to perceive the new (Laugier, 2013).

Ethics is basically a state of mind, a constantly renewed and nimble response to reality as it changes.

The ethics of care has emphasized attention as a critical component of ethics (Tronto, 1993: 127).

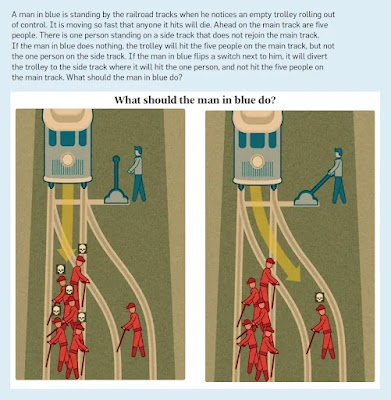

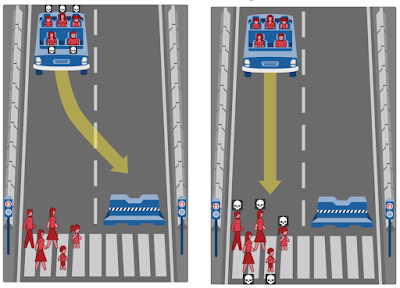

In this way, ethics is a strong instrument against cognitive and perceptual inertia, which prevents us from seeing what is different from before or in new settings, cultures, or circumstances, and hence necessitates a change in behavior (regulation included).

This is particularly important for AI, given the significant changes and implications it has had and continues to have on society, as well as our basic ways of being and functioning.

This ability to observe the environment is what keeps us from being cooked alive like the frog: it allows us to detect subtle changes as they happen.

An extension and deepening of monitoring by governments and commercial enterprises, a rising reliance on technology, and the deployment of biased systems that lead to discrimination against women and minorities are all contributing to the increasingly hot water in AI.

The positive changes they bring to society must be carefully examined and opposed when their negative consequences exceed their advantages.

In this way, ethics has a tight relationship with social sciences, as an attempt to perceive what we don't otherwise notice, and ethics aids us in looking concretely at how the world evolves.

It aids in the cleaning of the lens through which we see the world so that we may be more aware of its changes (and AI does bring many of these).

It is critical that ethics back us up in this respect.

It enables us to be less passive in the face of these changes, allowing us to better direct them in ways that benefit people and society while also improving our quality of life.

Hagendorff makes a similar point in his essay on the 'Ethics of AI Ethics,' disputing the prevalent deontological approach to ethics in AI ethics (what we've referred to as a legalistic approach to ethics in this article), whose primary goal is to 'limit, control, or direct' (2020: 112).

He emphasizes the necessity for AI to adopt virtue ethics, which strives to 'broaden the scope of action, disclose blind spots, promote autonomy and freedom, and cultivate self-responsibility' (Hagendorff, 2020: 112).

Other ethical theory frameworks that might be useful in today's AI ethics discussion include the Spinozist approach, which focuses on the growth or loss of agency and action capability.

So, are we just misinterpreting AI ethics, which, as we've seen, is now dominated by a 'law-concept of ethics'? Is today's legalistic approach to ethics entirely incorrect? No, not at all.

The problem is that principles, norms, and values — the legal definition of ethics that is so prevalent in AI ethics today – are more of a means to a goal than an end in themselves.

The word "end" has two meanings in this context.

First, it is an end of ethics in the sense that it is the last destination of ethics, i.e., moulding laws, choices, behaviors, and acts in ways that are consistent with society's ideals.

Ethics may be defined as the creation of principles (as in the AI HLEG criteria) or the application of ethical principles, values, or standards to particular situations.

This process of operationalization of ethical standards may be observed, for example, in the European Commission's research funding program's Ethics evaluation procedure5 or in ethics impact assessments, which look at how a new technique or technology could alter ethical norms and values.

These are unquestionably worthwhile endeavors that have a beneficial influence on society and people.

Ethics, as the development of principles, is also useful in shaping policies and regulatory frameworks.

The AI HLEG guidelines are heavily influenced by current policy and legislative developments at the EU level, such as the European Commission's "White Paper on Artificial Intelligence" (February 2020) and the European Parliament's proposed "Framework of ethical aspects of artificial intelligence, robotics, and related technologies" (April 2020).

Ethics clearly lays forth the rights and wrongs, as well as what should be done and what should be avoided.

It's important to recall, however, that ethics as ethical principles is also an end of ethics in another meaning: where it comes to a halt, where the thought is paused, and where this never-ending attention comes to an end.

As a result, when ethics is reduced to a collection of principles, norms, or criteria, it has achieved its conclusion.

There is no need for ethics if we have attained a sufficient degree of certainty and confidence in what are the correct judgments and acts.

Ethics is about navigating muddy and dangerous seas while being vigilant.

In the realm of AI, for example, ethical standards do not, by themselves, assist in the practical exploration of difficult topics such as fairness in extremely complex socio-technical systems.

These must be thoroughly studied to ensure that we are not putting in place systems that violate deeply held norms and beliefs.

Ethics is made worthless without a continual process of challenging what is or may be clear, of probing behind what seems to be resolved, and of keeping this inquiry alive.

As a result, the process of settling ethics into established norms and principles comes to an end.

It is vital to maintain ethics nimble and alive in light of AI's profound, huge, and broad influence on society.

The ongoing renewal process of examining the world and the glasses through which we experience it — intentionally, consistently, and iteratively – is critical to AI ethics.

~ Jai Krishna Ponnappan

You may also want to read more about Artificial Intelligence here.

See also:

AI ethics, law of AI, regulation of AI, ethics washing, EU HLEG on AI, ethical principles

Download PDF:

Further Reading:

- Anscombe, GEM (1958) Modern moral philosophy. Philosophy 33(124): 1–19.

- European Committee for Standardization (2017) CEN Workshop Agreement: Ethics assessment for research and innovation – Part 2: Ethical impact assessment framework (by the SATORI project). Available at: https://satoriproject.eu/media/CWA17145-23d2017 .

- Boddington, P (2017) Towards a Code of Ethics for Artificial Intelligence. Cham: Springer.

- European Parliament JURI (April 2020) Framework of ethical aspects of artificial intelligence, robotics and related technologies, draft report (2020/2012(INL)). Available at: https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/popups/ficheprocedure.do?lang=&reference=2020/2012 .

- Gilligan, C (1982) In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Floridi, L (2019) Translating principles into practices of digital ethics: Five risks of being unethical. Philosophy & Technology 32: 185–193.

- Greene, D, Hoffmann, A, Stark, L (2019) Better, nicer, clearer, fairer: A critical assessment of the movement for ethical artificial intelligence and machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii international conference on system sciences, Maui, Hawaii, 2019, pp.2122–2131.

- Gilligan, C (1982) In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hagendorff, T (2020) The ethics of AI ethics. An evaluation of guidelines. Minds and Machines 30: 99–120.

- Greene, D, Hoffmann, A, Stark, L (2019) Better, nicer, clearer, fairer: A critical assessment of the movement for ethical artificial intelligence and machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii international conference on system sciences, Maui, Hawaii, 2019, pp.2122–2131.

- Jansen P, Brey P, Fox A, Maas J, Hillas B, Wagner N, Smith P, Oluoch I, Lamers L, van Gein H, Resseguier A, Rodrigues R, Wright D, Douglas D (2019) Ethical analysis of AI and robotics technologies. August, SIENNA D4.4, https://www.sienna-project.eu/digitalAssets/801/c_801912-l_1-k_d4.4_ethical-analysis–ai-and-r–with-acknowledgements.pdf

- High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (2019) Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai

- Jansen P, Brey P, Fox A, Maas J, Hillas B, Wagner N, Smith P, Oluoch I, Lamers L, van Gein H, Resseguier A, Rodrigues R, Wright D, Douglas D (2019) Ethical analysis of AI and robotics technologies. August, SIENNA D4.4, https://www.sienna-project.eu/digitalAssets/801/c_801912-l_1-k_d4.4_ethical-analysis–ai-and-r–with-acknowledgements.pdf .

- Jobin, A, Ienca, M, Vayena, E (2019) The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nature Machine Intelligence 1(9): 389–399.

- Laugier, S (2013) The will to see: Ethics and moral perception of sense. Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal 34(2): 263–281.

- Klöver, C, Fanta, A (2019) No red lines: Industry defuses ethics guidelines for artificial intelligence. Available at: https://algorithmwatch.org/en/industry-defuses-ethics-guidelines-for-artificial-intelligence/

- López, JJ, Lunau, J (2012) ELSIfication in Canada: Legal modes of reasoning. Science as Culture 21(1): 77–99.

- Rodrigues, R, Rességuier, A (2019) The underdog in the AI ethical and legal debate: Human autonomy. In: Ethics Dialogues. Available at: https://www.ethicsdialogues.eu/2019/06/12/the-underdog-in-the-ai-ethical-and-legal-debate-human-autonomy/

- Ochigame, R (2019) The invention of “Ethical AI” how big tech manipulates academia to avoid regulation. The Intercept. Available at: https://theintercept.com/2019/12/20/mit-ethical-ai-artificial-intelligence/?comments=1

- Mittelstadt, B (2019) Principles alone cannot guarantee ethical AI. Nature Machine Intelligence 1: 501–507.

- Tronto, J (1993) Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York: Routledge.

- Wagner, B (2018) Ethics as an escape from regulation: From ethics-washing to ethics-shopping. In: Bayamlioglu, E, Baraliuc, I, Janssens, L, et al. (eds) Being Profiled: Cogitas Ergo Sum: 10 Years of Profiling the European Citizen. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 84–89.