1942

The Three Laws of Robotics by science fiction author Isaac Asimov occur in the short tale "Runaround."

1943

Emil Post, a mathematician, talks about "production systems," a notion he adopted for the 1957 General Problem Solver.

1943

"A Logical Calculus of the Ideas of Immanent in Nervous Activity," a study by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts on a computational theory of neural networks, is published.

1944

The Teleological Society was founded by John von Neumann, Norbert Wiener, Warren McCulloch, Walter Pitts, and Howard Aiken to explore, among other things, nervous system communication and control.

1945

In his book How to Solve It, George Polya emphasizes the importance of heuristic thinking in issue solving.

1946

In New York City, the first of eleven Macy Conferences on Cybernetics gets underway. "Feedback Mechanisms and Circular Causal Systems in Biological and Social Systems" is the focus of the inaugural conference.

1948

Norbert Wiener, a mathematician, publishes Cybernetics, or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine.

1949

In his book The Organization of Behavior, psychologist Donald Hebb provides a theory for brain adaptation in human education: "neurons that fire together connect together."

1949

Edmund Berkeley's book Giant Brains, or Machines That Think, is published.

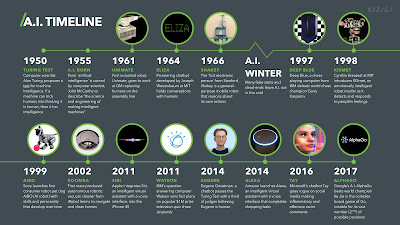

1950

Alan Turing's "Computing Machinery and Intelligence" describes the Turing Test, which attributes intelligence to any computer capable of demonstrating intelligent behavior comparable to that of a person.

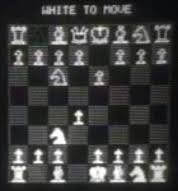

1950

Claude Shannon releases "Programming a Computer for Playing Chess," a groundbreaking technical study that shares search methods and strategies.

1951

Marvin Minsky, a math student, and Dean Edmonds, a physics student, create an electronic rat that can learn to navigate a labyrinth using Hebbian theory.

1951

John von Neumann, a mathematician, releases "General and Logical Theory of Automata," which reduces the human brain and central nervous system to a computer.

1951

For the University of Manchester's Ferranti Mark 1 computer, Christopher Strachey produces a checkers software and Dietrich Prinz creates a chess routine.

1952

Cyberneticist W. Edwards wrote Design for a Brain: The Origin of Adaptive Behavior, a book on the logical underpinnings of human brain function. Ross Ashby is a British actor.

1952

At Cornell University Medical College, physiologist James Hardy and physician Martin Lipkin begin developing a McBee punched card system for mechanical diagnosis of patients.

1954

Science-Fiction Thinking Machines: Robots, Androids, Computers, edited by Groff Conklin, is a theme-based anthology.

1954

The Georgetown-IBM project exemplifies the power of text machine translation.

1955

Under the direction of economist Herbert Simon and graduate student Allen Newell, artificial intelligence research began at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University).

1955

For Scientific American, mathematician John Kemeny wrote "Man as a Machine."

1955

In a Rockefeller Foundation proposal for a Dartmouth University meeting, mathematician John McCarthy coined the phrase "artificial intelligence."

1956

Allen Newell, Herbert Simon, and Cliff Shaw created Logic Theorist, an artificial intelligence computer software for proving theorems in Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell's Principia Mathematica.

1956

The "Constitutional Convention of AI," a Dartmouth Summer Research Project, brings together specialists in cybernetics, automata, information theory, operations research, and game theory.

1956

On television, electrical engineer Arthur Samuel shows off his checkers-playing AI software.

1957

Allen Newell and Herbert Simon created the General Problem Solver AI software.

1957

The Rockefeller Medical Electronics Center shows how an RCA Bizmac computer application might help doctors distinguish between blood disorders.

1958

The Computer and the Brain, an unfinished work by John von Neumann, is published.

1958

At the "Mechanisation of Thought Processes" symposium at the UK's Teddington National Physical Laboratory, Firmin Nash delivers the Group Symbol Associator its first public demonstration.

1958

For linear data categorization, Frank Rosenblatt develops the single layer perceptron, which includes a neural network and supervised learning algorithm.

1958

The high-level programming language LISP is specified by John McCarthy of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for AI research.

1959

"The Reasoning Foundations of Medical Diagnosis," written by physicist Robert Ledley and radiologist Lee Lusted, presents Bayesian inference and symbolic logic to medical difficulties.

1959

At MIT, John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky create the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

1960

James L. Adams, an engineering student, built the Stanford Cart, a remote control vehicle with a television camera.

1962

In his short novel "Without a Thought," science fiction and fantasy author Fred Saberhagen develops sentient killing robots known as Berserkers.

1963

John McCarthy developed the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (SAIL).

1963

Under Project MAC, the Advanced Research Experiments Agency of the United States Department of Defense began financing artificial intelligence projects at MIT.

1964

Joseph Weizenbaum of MIT created ELIZA, the first software allowing natural language conversation with a computer (a "chatbot").

1965

I am a statistician from the United Kingdom. J. Good's "Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine," which predicts an impending intelligence explosion, is published.

1965

Hubert L. Dreyfus and Stuart E. Dreyfus, philosophers and mathematicians, publish "Alchemy and AI," a study critical of artificial intelligence.

1965

Joshua Lederberg and Edward Feigenbaum founded the Stanford Heuristic Programming Project, which aims to model scientific reasoning and create expert systems.

1965

Donald Michie is the head of Edinburgh University's Department of Machine Intelligence and Perception.

1965

Georg Nees organizes the first generative art exhibition, Computer Graphic, in Stuttgart, West Germany.

1965

With the expert system DENDRAL, computer scientist Edward Feigenbaum starts a ten-year endeavor to automate the chemical analysis of organic molecules.

1966

The Automatic Language Processing Advisory Committee (ALPAC) issues a cautious assessment on machine translation's present status.

1967

On a DEC PDP-6 at MIT, Richard Greenblatt finishes work on Mac Hack, a computer that plays competitive tournament chess.

1967

Waseda University's Ichiro Kato begins work on the WABOT project, which culminates in the unveiling of a full-scale humanoid intelligent robot five years later.

1968

Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of Arthur C. Clarke's science fiction novel 2001: A Space Odyssey, about the artificially intelligent computer HAL 9000, is one of the most influential and highly praised films of all time.

1968

At MIT, Terry Winograd starts work on SHRDLU, a natural language understanding program.

1969

Washington, DC hosts the First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI).

1972

Artist Harold Cohen develops AARON, an artificial intelligence computer that generates paintings.

1972

Ken Colby describes his efforts using the software program PARRY to simulate paranoia.

1972

In What Computers Can't Do, Hubert Dreyfus offers his criticism of artificial intelligence's intellectual basis.

1972

Ted Shortliffe, a doctorate student at Stanford University, has started work on the MYCIN expert system, which is aimed to identify bacterial illnesses and provide treatment alternatives.

1972

The UK Science Research Council releases the Lighthill Report on Artificial Intelligence, which highlights AI technological shortcomings and the challenges of combinatorial explosion.

1972

The Assault on Privacy: Computers, Data Banks, and Dossiers, by Arthur Miller, is an early study on the societal implications of computers.

1972

INTERNIST-I, an internal medicine expert system, is being developed by University of Pittsburgh physician Jack Myers, medical student Randolph Miller, and computer scientist Harry Pople.

1974

Paul Werbos, a social scientist, has completed his dissertation on a backpropagation algorithm that is currently extensively used in artificial neural network training for supervised learning applications.

1974

The memo discusses the notion of a frame, a "remembered framework" that fits reality by "changing detail as appropriate." Marvin Minsky distributes MIT AI Lab document 306 on "A Framework for Representing Knowledge."

1975

The phrase "genetic algorithm" is used by John Holland to explain evolutionary strategies in natural and artificial systems.

1976

In Computer Power and Human Reason, computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum expresses his mixed feelings on artificial intelligence research.

1978

At Rutgers University, EXPERT, a generic knowledge representation technique for constructing expert systems, becomes live.

1978

Joshua Lederberg, Douglas Brutlag, Edward Feigenbaum, and Bruce Buchanan started the MOLGEN project at Stanford to solve DNA structures generated from segmentation data in molecular genetics research.

1979

Raj Reddy, a computer scientist at Carnegie Mellon University, founded the Robotics Institute.

1979

While working with a robot, the first human is slain.

1979

Hans Moravec rebuilds and equips the Stanford Cart with a stereoscopic vision system after it has evolved into an autonomous rover over almost two decades.

1980

The American Association of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI) holds its first national conference at Stanford University.

1980

In his Chinese Room argument, philosopher John Searle claims that a computer's modeling of action does not establish comprehension, intentionality, or awareness.

1982

Release of Blade Runner, a science fiction picture based on Philip K. Dick's tale Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968).

1982

The associative brain network, initially developed by William Little in 1974, is popularized by physicist John Hopfield.

1984

In Fortune Magazine, Tom Alexander writes "Why Computers Can't Outthink the Experts."

1984

At the Microelectronics and Computer Consortium (MCC) in Austin, TX, computer scientist Doug Lenat launches the Cyc project, which aims to create a vast commonsense knowledge base and artificial intelligence architecture.

1984

Orion Pictures releases the first Terminator picture, which features robotic assassins from the future and an AI known as Skynet.

1986

Honda establishes a research facility to build humanoid robots that can cohabit and interact with humans.

1986

Rodney Brooks, an MIT roboticist, describes the subsumption architecture for behavior-based robots.

The Society of Mind is published by Marvin Minsky, who depicts the brain as a collection of collaborating agents.

1989

The MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab's Rodney Brooks and Anita Flynn publish "Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control: A Robot Invasion of the Solar System," a paper discussing the possibility of sending small robots on interplanetary exploration missions.

1993

The Cog interactive robot project is launched at MIT by Rodney Brooks, Lynn Andrea Stein, Cynthia Breazeal, and others.

1995

The phrase "generative music" was used by musician Brian Eno to describe systems that create ever-changing music by modifying parameters over time.

1995

The MQ-1 Predator unmanned aerial aircraft from General Atomics has entered US military and reconnaissance duty.

1997

Under normal tournament settings, IBM's Deep Blue supercomputer overcomes reigning chess champion Garry Kasparov.

1997

In Nagoya, Japan, the inaugural RoboCup, an international tournament featuring over forty teams of robot soccer players, takes place.

1997

NaturallySpeaking is Dragon Systems' first commercial voice recognition software product.

1999

Sony introduces AIBO, a robotic dog, to the general public.

2000

The Advanced Step in Innovative Mobility humanoid robot, ASIMO, is unveiled by Honda.

2001

At Super Bowl XXXV, Visage Corporation unveils the FaceFINDER automatic face-recognition technology.

2002

The Roomba autonomous household vacuum cleaner is released by the iRobot Corporation, which was created by Rodney Brooks, Colin Angle, and Helen Greiner.

2004

In the Mojave Desert near Primm, NV, DARPA hosts its inaugural autonomous vehicle Grand Challenge, but none of the cars complete the 150-mile route.

2005

Under the direction of neurologist Henry Markram, the Swiss Blue Brain Project is formed to imitate the human brain.

2006

Netflix is awarding a $1 million prize to the first programming team to create the greatest recommender system based on prior user ratings.

2007

DARPA has announced the commencement of the Urban Challenge, an autonomous car competition that will test merging, passing, parking, and navigating traffic and junctions.

2009

Under the leadership of Sebastian Thrun, Google launches its self-driving car project (now known as Waymo) in the San Francisco Bay Area.

2009

Fei-Fei Li of Stanford University describes her work on ImageNet, a library of millions of hand-annotated photographs used to teach AIs to recognize the presence or absence of items visually.

2010

Human manipulation of automated trading algorithms causes a "flash collapse" in the US stock market.

2011

Demis Hassabis, Shane Legg, and Mustafa Suleyman developed DeepMind in the United Kingdom to educate AIs how to play and succeed at classic video games.

2011

Watson, IBM's natural language computer system, has beaten Jeopardy! Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter are the champions.

2011

The iPhone 4S comes with Apple's mobile suggestion assistant Siri.

2011

Andrew Ng, a computer scientist, and Google colleagues Jeff Dean and Greg Corrado have launched an informal Google Brain deep learning research cooperation.

2013

The European Union's Human Brain Project aims to better understand how the human brain functions and to duplicate its computing capabilities.

2013

Stop Killer Robots is a campaign launched by Human Rights Watch.

2013

Spike Jonze's science fiction drama Her has been released. A guy and his AI mobile suggestion assistant Samantha fall in love in the film.

2014

Ian Goodfellow and colleagues at the University of Montreal create Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for use in deep neural networks, which are beneficial in making realistic fake human photos.

2014

Eugene Goostman, a chatbot that plays a thirteen-year-old kid, is said to have passed a Turing-like test.

2014

According to physicist Stephen Hawking, the development of AI might lead to humanity's extinction.

2015

DeepFace is a deep learning face recognition system that Facebook has released on its social media platform.

2016

In a five-game battle, DeepMind's AlphaGo software beats Lee Sedol, a 9th dan Go player.

2016

Tay, a Microsoft AI chatbot, has been put on Twitter, where users may teach it to send abusive and inappropriate posts.

2017

The Asilomar Meeting on Beneficial AI is hosted by the Future of Life Institute.

2017

Anthony Levandowski, an AI self-driving start-up engineer, formed the Way of the Future church with the goal of creating a superintelligent robot god.

2018

Google has announced Duplex, an AI program that uses natural language to schedule appointments over the phone.

2018

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and "Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI" are published by the European Union.

2019

A lung cancer screening AI developed by Google AI and Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, IL, surpasses specialized radiologists.

2019

Elon Musk cofounded OpenAI, which generates realistic tales and journalism via artificial intelligence text generation. Because of its ability to spread false news, it was previously judged "too risky" to utilize.

2020

TensorFlow Quantum, an open-source framework for quantum machine learning, was announced by Google AI in conjunction with the University of Waterloo, the "moonshot faculty" X, and Volkswagen.

Find Jai on Twitter | LinkedIn | Instagram

You may also want to read more about Artificial Intelligence here.