Because of the growth of artificial intelligence (AI) and

robots and their application to military matters, generals on the contemporary

battlefield are seeing a possible tactical and strategic revolution.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), also known as drones, and

other robotic devices played a key role in the wars in Afghanistan (2001–) and

Iraq (2003–2011).

It is possible that future conflicts will be waged without

the participation of humans.

Without human control or guidance, autonomous robots will

fight in war on land, in the air, and beneath the water.

While this vision remains in the realm of science fiction,

battlefield AI and robotics raise a slew of practical, ethical, and legal

issues that military leaders, technologists, jurists, and philosophers must

address.

When many people think about AI and robotics on the

battlefield, the first image that springs to mind is "killer robots,"

armed machines that indiscriminately destroy everything in their path.

There are, however, a variety of applications for

battlefield AI that do not include killing.

In recent wars, the most notable application of such

technology has been peaceful in character.

UAVs are often employed for surveillance and reconnaissance.

Other robots, like as iRobot's PackBot (the same firm that

makes the vacuum-cleaning Roomba), are employed to locate and assess improvised

explosive devices (IEDs), making their safe disposal easier.

Robotic devices can navigate treacherous terrain, such as

Afghanistan's caves and mountain crags, as well as areas too dangerous for

humans, such as under a vehicle suspected of being rigged with an IED.

Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) are also used to detect

mines underwater.

IEDs and explosives are so common on today's battlefields

that these robotic gadgets are priceless.

Another potential life-saving capacity of battlefield robots

that has yet to be realized is in the realm of medicine.

Robots can safely collect injured troops on the battlefield

in areas that are inaccessible to their human counterparts, without

jeopardizing their own lives.

Robots may also transport medical supplies and medications

to troops on the battlefield, as well as conduct basic first aid and other

emergency medical operations.

AI and robots have the greatest potential to change the

battlefield—whether on land, sea, or in the air—in the arena of deadly power.

The Aegis Combat System (ACS) is an example of an autonomous

system used by several militaries across the globe aboard destroyers and other

naval combat vessels.

Through radar and sonar, the system can detect approaching

threats, such as missiles from the surface or air, mines, or torpedoes from the

water.

The system is equipped with a powerful computer system and

can use its own munitions to eliminate identified threats.

Despite the fact that Aegis is activated and supervised

manually, it has the potential to operate autonomously in order to counter

threats faster than humans could.

In addition to partly automated systems like the ACS and

UAVs, completely autonomous military robots capable of making judgments and

acting on their own may be developed in the future.

The most significant feature of AI-powered robotics is the

development of lethal autonomous weapons (LAWs), sometimes known as

"killer robots." On a sliding scale, robot autonomy exists.

At one extreme of the spectrum are robots that are designed

to operate autonomously, but only in reaction to a specific stimulus and in one

direction.

This degree of autonomy is shown by a mine that detonates

autonomously when stepped on.

Remotely operated machines, which are unmanned yet

controlled remotely by a person, are also available at the lowest end of the

range.

Semiautonomous systems occupy the midpoint of the spectrum.

These systems may be able to work without the assistance of

a person, but only to a limited extent.

A robot commanded to launch, go to a certain area, and then

return at a specific time is an example of such a system.

The machine does not make any "decisions" on its

own in this situation.

Semiautonomous devices may also be configured to accomplish

part of a task before waiting for further inputs before moving on to the next

step.

Full autonomy is the last step.

Fully autonomous robots are designed with a purpose and are

capable of achieving it entirely on their own.

This might include the capacity to use deadly force without

direct human guidance in warfare circumstances.

Robotic gadgets that are lethally equipped, AI-enhanced, and

totally autonomous have the ability to radically transform the current warfare.

Military ground troops made up of both humans and robots, or

entirely of robots with no humans, would expand armies.

Small, armed UAVs would not be constrained by the

requirement for human operators, and they might be assembled in massive swarms

to overwhelm bigger, but less mobile troops.

Such technological advancements will entail equally dramatic

shifts in tactics, strategy, and even the notion of combat.

This technology will become less expensive as it becomes

more widely accessible.

This might disturb the present military power balance.

Even minor governments, and maybe even non-state

organizations like terrorist groups, may be able to develop their own robotic

army.

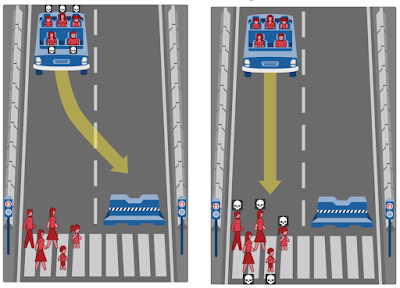

Fully autonomous LAWs bring up a slew of practical, ethical,

and legal issues.

One of the most pressing practical considerations is safety.

A completely autonomous robot with deadly armament that

malfunctions might represent a major threat to everyone who comes in contact

with it.

Fully autonomous missiles might theoretically wander off

course and kill innocent people due to a mechanical failure.

Unpredictable technological faults and malfunctions may

occur in any kind of apparatus.

Such issues offer a severe safety concern to individuals who

deploy deadly robotic gadgets as well as unwitting bystanders.

Even if there are no possible problems, restrictions in

program ming may result in potentially disastrous errors.

Programming robots to discriminate between combatants and

noncombatants, for example, is a big challenge, and it's simple to envisage

misidentification leading to unintentional fatalities.

The greatest concern, though, is that robotic AI may grow

too quickly and become independent of human control.

Sentient robots might turn their armament on humans, like in

popular science fiction movies and literature, and in fulfillment of eminent

scientist Stephen Hawking's grim forecast that the development of AI could end

in humanity's annihilation.

Laws may also lead to major legal issues.

The rules of war apply to human beings.

Robots cannot be held accountable for prospective law

crimes, whether criminally, civilly, or in any other manner.

As a result, there's a chance that war crimes or other legal

violations may go unpunished.

Here are some serious issues to consider: Can the programmer

or engineer of a robot be held liable for the machine's actions? Could a person

who gave the robot its "command" be held liable for the robot's

unpredictability or blunders on a mission that was otherwise self-directed?

Such considerations must be thoroughly considered before any completely

autonomous deadly equipment is deployed.

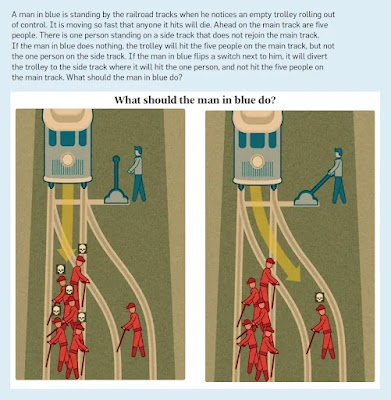

Aside from legal issues of duty, a slew of ethical issues

must be addressed.

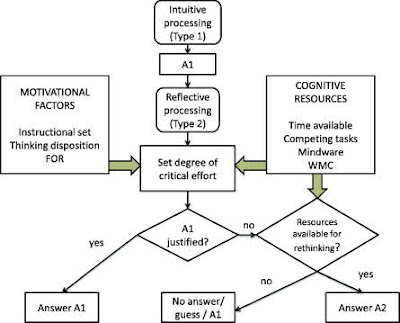

The conduct of war necessitates split-second moral

judgments.

Will self-driving robots be able to tell the difference between

a kid and a soldier, or between a wounded and helpless soldier and an active

combatant? Will a robotic military force always be seen as a cold, brutal, and

merciless army of destruction, or can a robot be designed to behave kindly when

the situation demands it? Because combat is riddled with moral dilemmas, LAWs

involved in war will always be confronted with them.

Experts wonder that dangerous autonomous robots can ever be

trusted to do the right thing.

Moral action requires not just rationality—which robots may

be capable of—but also emotions, empathy, and wisdom.

These later items are much more difficult to implement in

code.

Many individuals have called for an absolute ban on research

in this field because to legal, ethical, and practical problems highlighted by

the potential of ever more powerful AI-powered robotic military hardware.

Others, on the other hand, believe that scientific

advancement cannot be halted.

Rather than prohibiting such study, they argue that

scientists and society as a whole should seek realistic answers to the

difficulties.

Some argue that keeping continual human supervision and

control over robotic military units may address many of the ethical and legal

issues.

Others argue that direct supervision is unlikely in the long

term because human intellect will be unable to match the pace with which

computers think and act.

As the side that gives its robotic troops more autonomy

gains an overwhelming advantage over those who strive to preserve human

control, there will be an inevitable trend toward more and more autonomy.

They warn that fully autonomous forces will always triumph.

Despite the fact that it is still in its early stages, the

introduction of more complex AI and robotic equipment to the battlefield has

already resulted in significant change.

AI and robotics on the battlefield have the potential to

drastically transform the future of warfare.

It remains to be seen if and how this technology's

technical, practical, legal, and ethical limits can be addressed.

~ Jai Krishna Ponnappan

You may also want to read more about Artificial Intelligence here.

See also:

Autonomous Weapons Systems, Ethics of; Lethal Autonomous Weapons

Systems.

Further Reading

Borenstein, Jason. 2008. “The Ethics of Autonomous Military Robots.” Studies in Ethics,

Law, and Technology 2, no. 1: n.p. https://www.degruyter.com/view/journals/selt/2/1/article-selt.2008.2.1.1036.xml.xml.

Morris, Zachary L. 2018. “Developing a Light Infantry-Robotic Company as a System.”

Military Review 98, no. 4 (July–August): 18–29.

Scharre, Paul. 2018. Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War. New

York: W. W. Norton.

Singer, Peter W. 2009. Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st

Century. London: Penguin.

Sparrow, Robert. 2007. “Killer Robots,” Journal of Applied Philosophy 24, no. 1: 62–77.